Truth-Telling in Narrative Non-Fiction and Memoir: Where Should Your Allegiances Lie?

“All I knew was that I had to tell the truth.”-Maya Angelou

“The truth will set you free. But first it will piss you off.” -Author Unknown

I love that Maya Angelou quote. It’s often referenced by writers who are steadfastly dedicating themselves to telling the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

I also really like the second quote. Its origins are opaque (for more on that, click here), but every writer contends with its implied warning at some point or another.

The human impulse to truthiness is easy to understand. Whether it’s fiction or non-fiction, most writers pull from their own experiences for inspiration, and unless you were raised in a fallout shelter, your personal experiences probably involve other people. Yep! Real, live people, who might actually — gulp! — read what you wrote about them.

(On second thought, that’s actually probably even true if you came up in a fallout shelter.)

Memoir and non-fiction writing in particular are not for the faint of heart! What if your loved ones don’t take kindly to the way you’ve represented them? What if they grumble and object or, worse, emphatically deny having said and done some of the things you are fairly certain they did say and do?

The situation gets sticky fast.

My general advice on the matter is: It’s better to beg forgiveness than to ask permission when writing about people you know. And this means not showing your works-in-progress to loved ones without a darned good reason. And if you do decide to show your work, it’s wise to err on the side of not changing it unless it’s factually incorrect, as you set a dangerous precedent for the fungibility of future writing. This is your story; not theirs. And your story belongs only to you.

But in real life, it’s not always that simple. Especially if these are people you care about. Sometimes, concerns over accuracy and courtesy trump abstract proclamations like the ones I just made above.

If you do decide to show your work, I’d entreat you to wait, at the very least, till you’re all way through the writing and editing process.

At that point, there are two kinds of “reads” you might offer someone you care about:

The Courtesy Read: If you show your work to someone out of simple courtesy or to sate their curiosity, it’s important to be clear about your boundaries in advance. Are you asking for their opinion or their blessing? Or just giving them a head’s up? Do you want any feedback or edits? And how will you handle the feedback you do get (whether you asked for it or not!)?

The Accuracy Read: This process is little more cut-and-dry, and might even be required by your editor or publisher. Here, your main concern is getting the facts of a true story right. This is most easily accomplished by sending the person in question a list of free-standing quotes and statements involving them directly and asking them to confirm their accuracy rather than sending the entire piece. You’ll also want to be explicit about whether you are willing to consider edits or additions beyond the scope of factuality.

In either case, it’s helpful to work through a few general questions on your own in advance.

Before You Share Your Writing with Someone, Ask Yourself:

· Do I care about this person enough to care whether they like how they’ve been represented? If not, why am I sharing this?

· What will I do if they come back with an extensive list of qualms or edits, even if I said I wasn’t open to them?

· What if they are more neutral on my story but remember events differently?

· What if they are ashamed or embarrassed or just plain furious with me for resurrecting the past on paper?

· What if they like the piece but have well-meaning suggestions or additions that I’m just not interested in implementing?

· If I don’t send them the whole piece and they later ask to see it, what will I say?

· And, hairiest of all: What will I do if they ask me not to write about them or not to publish the story at all?

The Hard Conversation

Sometimes, you get lucky and your loved one has nothing but praise to heap upon you and your writing. If this happens, good on you!

If this doesn’t happen, you’ll need to prepare for an awkward conversation, and you’ll ultimately need to make one of three choices regarding the writing at issue: Cut it, change it, or leave it be.

Prepare for the awkward conversation by revisiting your answers to the above questions, reaffirming your boundaries, and steeling yourself to enforce them if needed. And be ready, also, to listen deeply and compassionately, even if you plan to stand your ground!

A few questions to consider as you work through things with your loved one:

Are they asking to me to change something, or do they just want to have their feelings heard? A little validation can go a long way. Let your loved one talk, and ask them meaningful questions to get to the root of what’s at issue. Are they embarrassed? Triggered? Just reacting? Don’t pander or apologize, but if you seem to have differing memories or levels of comfort about the subject matter, acknowledge that, and acknowledge that it’s hard to be somebody else’s copy. Explain, too, why this story is important to you and why you feel the need to tell it in this way and see if you can’t find a bit of shared understanding.

Is the request reasonable? People are sensitive to the ways they are memorialized, especially when their less-flattering moments are forever enshrined in print or web for all to see (and judge). And writers, too, are sensitive to being critiqued, especially when they’ve worked hard on a piece and believe the telling to be factual. Proceed with pragmatism: Is the person questioning your recollection of a silly-but-unflattering anecdote, or are they insisting that you scrap a story entirely? Does this information have the potential to humiliate them in a way that is not deserved or earned? Can you make the change without sacrificing the integrity of your piece or needing to rework large chunks of it? If not, you may need to prepare your counterargument. (And as a rule, expect way more pushback when you use direct quotes! People love claiming they didn’t say things that they actually did say.)

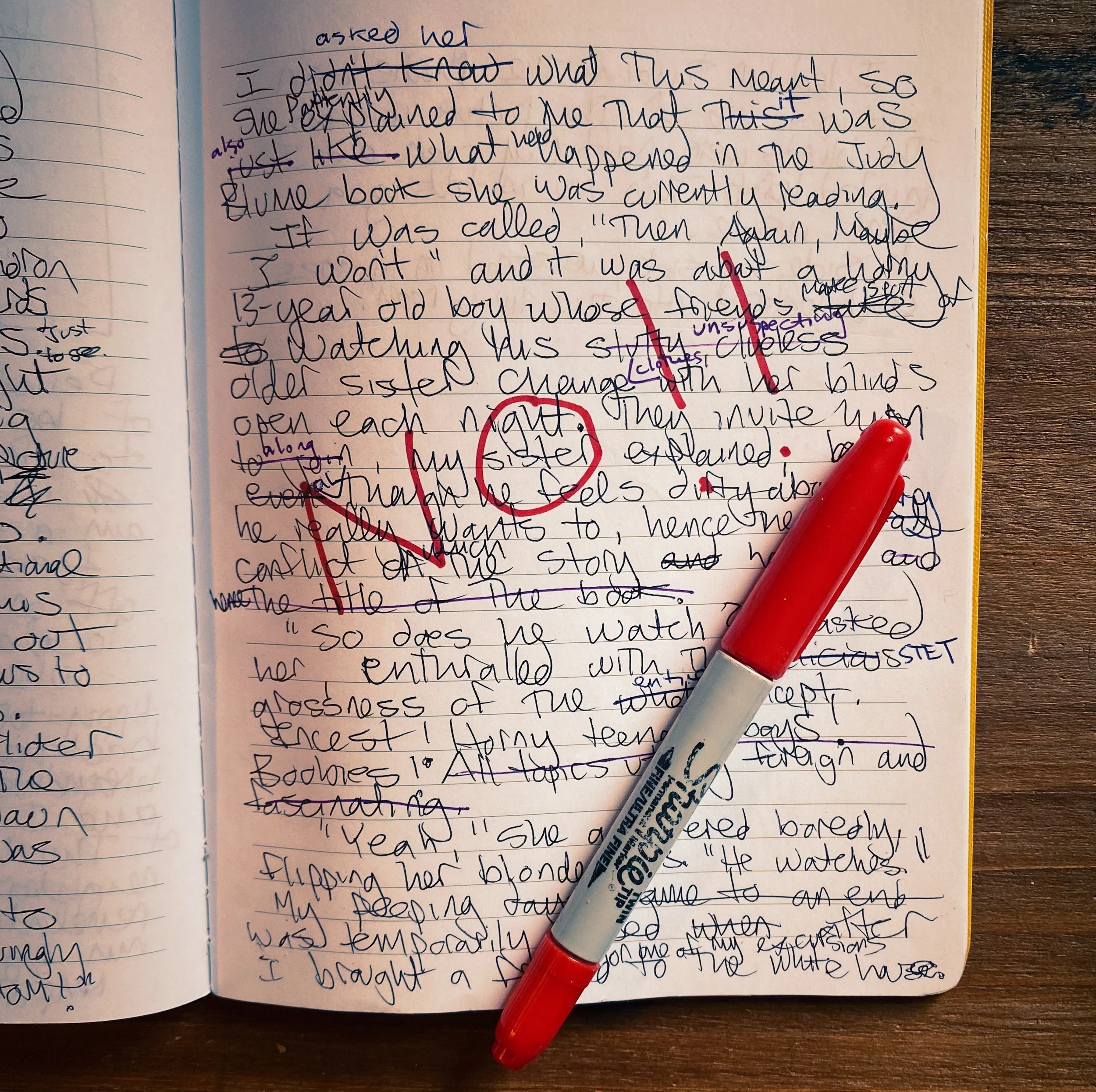

Can I back up my claims? Fiction writers can simply remind protesters that they’re describing a poetic reality, but if you write non-fiction, you might need to try and corroborate your words and facts. Is any of this in writing or on video/photo somewhere? Can you track down somebody else who was there and mine their memory? And keep in mind: Our memories can be shockingly inaccurate, so don’t get too cocky right off the bat. You may swear up and down that you recall verbatim the eulogy your sister gave at a funeral, only to track down a recording of the service and discover that she wasn’t even there. People misremember. Even people who normally remember quite well. So back up your truths whenever you can.

Can we compromise? Yes, yes, I know: Your writing is your art, your words the chicken-scratch equivalent of the Sistine Chapel, your finished pieces a sincere and earnest gift to posterity. But let’s be realistic: Nobody writes in a vacuum, and if the person in question is important in your life, you may need to compromise in order to maintain the peace. If the complainant is a family member, the implications of failing to do so could be even more dramatic and long-lasting. Can you omit a name or some of the information, or even acknowledge in the piece that this person remembers things differently? Would a different anecdote illustrate the same idea? If not, that’s fine! But can you sit down with this person and explain to them, calmly and sincerely, where you are coming from? Sometimes, they’ll even be the one to offer up a reasonable middle ground.

What’s more important – The piece or this person’s feelings? This is not a trick question; sometimes, as Ms. Angelou says, telling the truth absolutely matters more than anything else. No matter the consequence, and even when the person asking you to reconsider is somebody you love quite a lot. Is this a story you can’t imagine taking to your grave, like, the story you’ve been trying to figure out how to tell for half of your life, or is it simply a humorous piece you pounded out on a Tuesday afternoon in order to blow off some steam? And are they merely embarrassed or annoyed about what you want to say, or are they straight-up horrified? Embarrassment and annoyance fade with time. Mortification does not.

What’s truly at stake? It’s never just a story; it’s your craft, your time, your labor. But some pieces matter more to us as writers than other pieces do. Take some time to clearly identify what’s at stake, both in the piece and in your relationship. The stakes might be low — you’re recounting the sordid tale of a friend who peed her pants on the bus during a third-grade field trip to the zoo — and they may be sky-high — you’re writing a first-person memoir about how the bus driver on that field trip turned out to be a jewel thief on the lam. What’s on the line? Will the piece lose something significant if you cut a disliked fact? Will your relationship with this person be forever changed if you don’t? Ultimately, what do you stand to lose?

All people are created equal; all writing is not. Be honest with yourself about how much the piece and the person’s feelings about it truly matter. Weigh one against the other and decide: Cut it, change it, or leave it be.

Then, make peace with your choice and move on.

Truth tellin’ ain’t easy; the most important work rarely is.